I have a huge problem with Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, but before I get to that I need to make a confession up front: I’m not a huge Miyazaki fan. This may make you discount all that comes after, and I guess that’s fair enough. The Wind Rises was already had an uphill battle for me, as I’ve never been particularly enthusiastic about Miyazaki’s aesthetic; Spirited Away is the Miyazaki film that worked the most for me, and while I certainly appreciate the artistry of his films they rarely truly connect with me. That’s a personal thing, and it’s probably important to note.

That could be part of why the film itself left me a little cold; it’s very long and doesn’t even have the whimsy of previous Miyazaki films. It’s the true story of Jiro Horikoshi, the man who designed the feared and famed Japanese Zero fighter planes. It’s a film that indulges in Miyazaki’s love of aviation, and it’s a film that explores the meaning of creation and obsession. It’s also a film that’s about a guy who creates weapons of war because he likes to design planes, but who never has a moment’s conflict about this.

Basically the film follows Jiro from childhood, where he dreams of flying but cannot become a pilot due to his eyesight, to the beginnings of WWII, as his Zero planes fly off to Pearl Harbor. He’s a man driven by his love for flight, who dreams of nothing but planes, and whose every waking moment is spent working on the engineering problems that will allow Japan to build all-metal planes and give them the opportunity to enter the global arena of modern war. Jiro isn’t looking to design war planes, but from his very earliest days he understands that the beautiful machines he loves will be used to kill people.

And he’s pretty okay with it.

This is where my interpretation of the film might diverge from others, but for me The Wind Rises is a movie about the purity of creation, an argument that the artist cannot be responsible for how his art is used. During the movie Jiro has dream conversations with Italian aviation pioneer Count Caproni, whose planes were used as bombers in WWI, and during one of those conversations Caproni asks Jiro a question that I think defines the film: would you rather live in a world with or without the Pyramids? The implication here is that despite being built by slaves, the Pyramids are wonders, and our world is better for them. The same implication extends to the war planes the men build - aviation is such a wonder that even though it is cursed to forever be used in war it’s better to have flight than not.

That’s an interesting - and totally defensible - attitude. Flight has changed the face of war, making it more brutal and distant, but it has also changed the relationships of human beings across the globe, making the Earth a smaller and more connected place. There is a trade-off, and it’s the nature of all creative and engineering works - you make things and they are used as they are used.

But Jiro isn’t making planes that are then being used by the military - he’s making planes for the military. There’s a scene where he’s doing a design seminar with other engineers and he shows a design for an elegant, fast plane… that will not work with guns on it. So he laughs and says he threw away that design. Because he’s designing planes that will carry guns and bombs, and that’s what their purpose is in every way. This never seems to bother him; even as other characters explain to him that Japan and ally Germany are headed for trouble he doesn’t seem to care. He just wants to design planes, and military contracts are what will allow him to do that.

There’s something else Jiro loves - a doomed girl with tuberculosis who he marries despite her illness. Her decline is played as a counterpoint to Jiro’s engineering successes - the better he gets at making war planes, the sicker she gets. But the intended echo doesn’t work, especially as it’s weird to make the argument that Jiro’s work in the industry of death harms him by… making his wife sick.

The narrative problem here is that Jiro ALWAYS KNOWS how his planes will be used. He dreams about it as a young man in school, even before Japan invades Manchuria. He has no illusions, and the fact that he has no illusions makes it seem as if he simply doesn’t care. Designing planes is more important than the morality of how those planes will be used. Miyazaki has said the film is about a man whose beautiful dreams are corrupted by war, but his dreams were compromised from the very beginning - his first flying dream is a war dream.

What’s more, the film has a weirdly ambivalent take on war for an avowed anti-war film. Early in the story there’s a huge earthquake that hits Tokyo and the city is laid waste. This imagery is repeated at the end, as Jiro precognitively dreams about the destruction that will be visited upon his nation when the US bombs. Visually Miyazaki is comparing the destruction of war with the destruction of a natural disaster. They’re both things that are out of our control.

If both are out of our control the only thing that matters is how we react to them. In the earthquake Jiro is heroic; while everyone else flees a derailed train, he goes back to help a woman whose leg is broken. Doing that brings him together with the young girl he eventually marries. But Jiro does nothing heroic about the natural disaster of WWII. He took action in the earthquake; all he had to do in the years leading up to WWII was not take action. And the film goes to pains to show that he was aware of what was happening around him.

Giving Jiro some conflict would have helped with the rest of the movie, where he basically just walks through life. He’s an engineering genius who excels at school and then excels at work and then keeps on excelling. He has few obstacles, which makes his moral apathy all the more irritating. I found him to be a remarkably boring character, and the scenes where he ecstatically disappears into equations with his slide rule never moved me. Every time Caproni showed up in Jiro’s dreams I wished we saw more of him - he’s a man of passion and philosophy. Jiro’s a nerd with little interest in anything else in life outside of the engineering problems of aviation.

The film is gorgeous, even though I always feel like Miyazaki’s animation style is a couple of frames away from being as fluid as I like. He keeps the movie very grounded and even Jiro’s dreams are less fantastical than previous films. Still, it’s all lovely, and Miyazaki captures a lyrical sense of Japanese life in the days before WWII, as the wind rises. I wish these beautiful scenes and images were in the service of a story that I enjoyed watching be told.

My moral objections aren’t based on national allegiances; I don’t care that Jiro’s planes were used to kill Americans. I care that they were used to kill humans. As Robert Oppenheimer saw the A-bomb he designed explode he said, with regret, “Now I am become Death, destroyed of worlds.” As Jiro looks walks through an imaginary wasteland littered with plane parts beneath a sky crowded with beautiful killing machines, he only laments that none of the planes came back. Right up until the end he only cares about the engineering. I can’t care for someone like that.

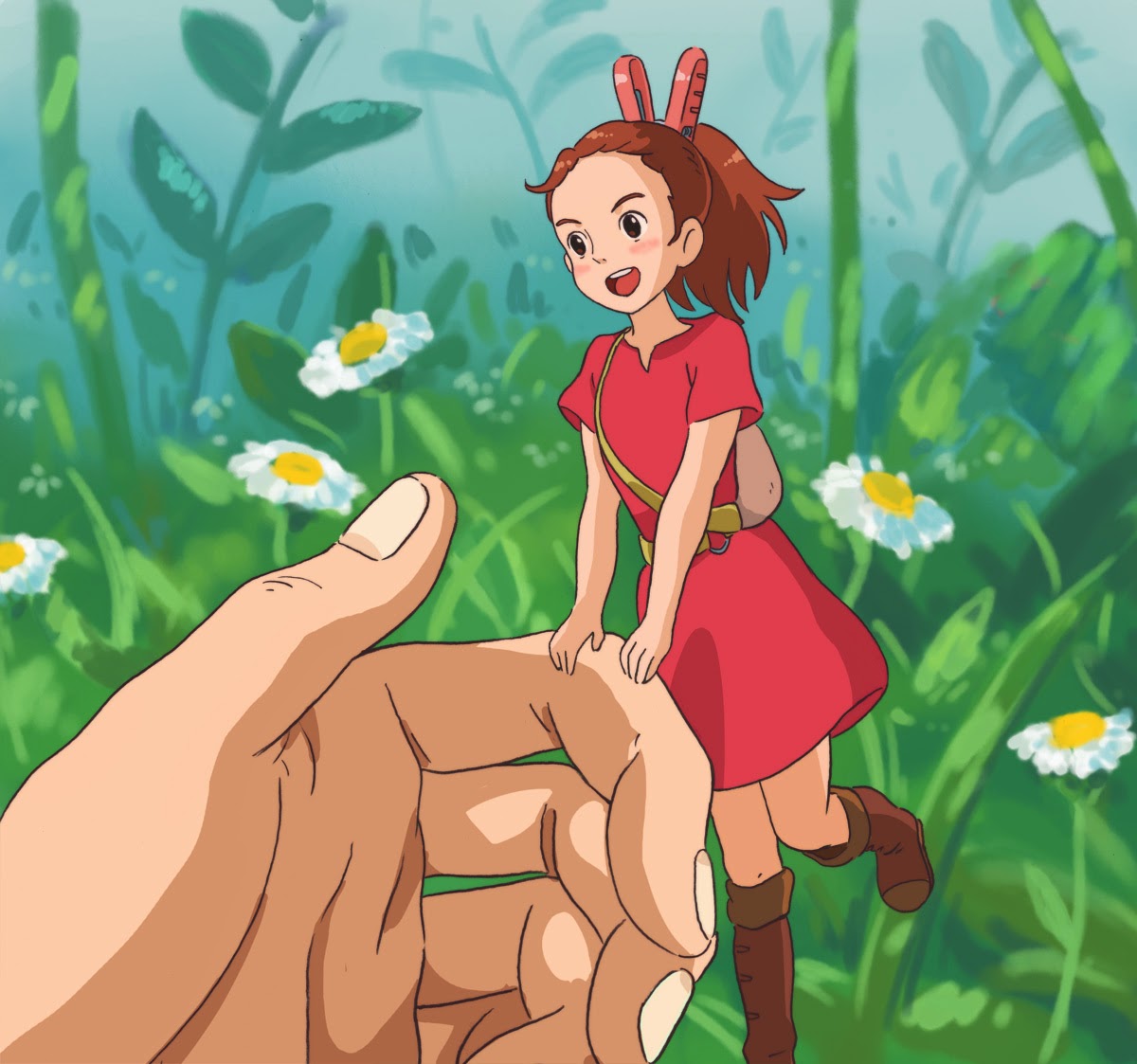

Her hair. When in her red dress, Arrietty had an orange clip in her hair, making her hair into a ponytail. If you want to recreate the scene where Arrietty and Sho go their separate ways, or if you are wearing her brown and white dress, skip this. If your hair is a different color, dye it brown.

Her hair. When in her red dress, Arrietty had an orange clip in her hair, making her hair into a ponytail. If you want to recreate the scene where Arrietty and Sho go their separate ways, or if you are wearing her brown and white dress, skip this. If your hair is a different color, dye it brown.

.jpg)